In 1943, The California School for Fine Arts (CSFA) in San Francisco (later known as the San Francisco Art Institute) hired Douglas MacAgy, famous in American art circles as a promoter and collector, as its new director. The school trustees wanted new energy and direction at the school and MacAgy delivered it. He promoted the school as the hub of Abstract Expressionism on the West Coast. As new members of the CSFA faculty, MacAgy hired Clyfford Still, Hassel Smith, David Park, Elmer Bischoff, Richard Diebenkorn and Mark Rothko. As instructors, Smith, Park, Bischoff and Diebenkorn received a living wage allowing them to support themselves and their families while still able to create their own work. Still and Rothko were already leaders of the Abstract Expressionists and the others were painting in that style as well.

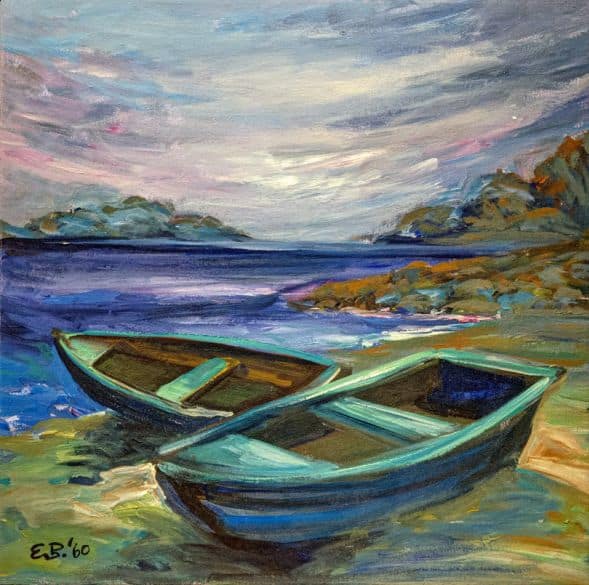

From the late 1940s through the early 1960s, the CSFA artists, while teaching art classes at the school and stressing Abstract Expressionism and its expression of emotion over imagery, began to turn to more traditional motifs in their own work. First David Park (and later Elmer Bischoff and Richard Diebenkorn) would begin to apply Abstract Expressionist techniques to figurative and objective paintings. As example, human figures or landscapes, while abstracted, were not created by careful brushstroke delineation but rather by a slathering application of pigment by palette knife. Art historian Caroline A. Jones, in her 1990 book “Bay Area Figurative Art 1950-1965,” characterizes such work as a “defection” from the original Abstract Expressionist school. These artists became known as the CSFA post-war movement. The New York “school” was more strongly committed to the style and technique of Abstract Expressionism; The San Francisco “school” developed a more relaxed interpretation of how modern art should be created and interpreted known as figurative expressionism.